CORPORATE| 10.11.2021

Edgar Abraham: “Saxophone is called an instrument because it’s an extension of the soul”

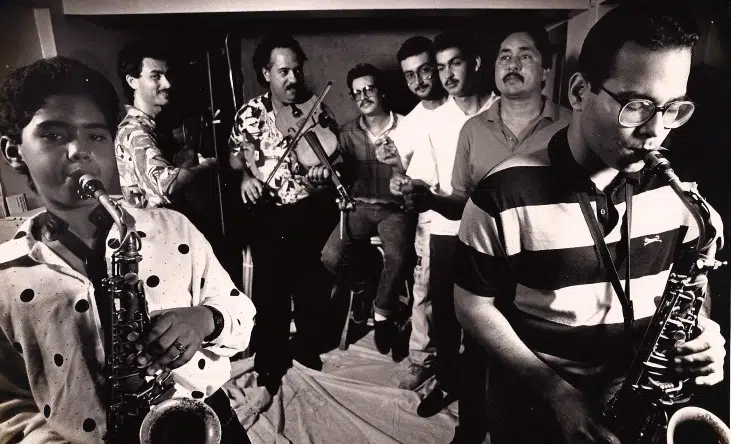

Edgar Abraham began playing the violin when he was three years old, thanks to his father, who was a member of the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra. He was introduced to jazz by his music teacher, Héctor Miranda, who he treats as a member of his family. Like everyone else featured in MAPFRE’s We believe in you, do you? campaign, this saxophone virtuoso emphasizes the importance of sacrifice, the willingness to make changes through effort, and the belief that personal growth begins on the inside. He has been awarded three Latin Grammys, but when he speaks it is with a spirit of humility and generosity. He claims he could never give up his saxophone or his music, because they are a part of who he is, eternal and inexhaustible, like his confidence.

You’ve been a virtuoso since you were a child. Has your family been an important part of your love for music?

You’ve been a virtuoso since you were a child. Has your family been an important part of your love for music?

I come from a musical family. My father is a violinist, and he was a member of the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra for 30 years. Although he’s retired now, he still plays. I was obviously exposed to classical music because of him, and to pop music too. My first memories are of my father playing his viola, and I also started playing that instrument a very young age. When you teach a child to play music, your goal might just be to give them the experience of playing music, so they know what it feels like. But for me, it went from being an experience to a commitment I made to myself, not just to my father. I began to realize that it was really about how much I could contribute. To become a better person, not just from a musical perspective. To understand how much I could grow, first as a human, and then as a musician. And that was the process I followed: one of natural introspection, with plenty of personal sacrifice.

…And your teacher, Héctor Miranda, was an important role model too, right?

Yes, from a very early age… Even after the classes I took with him had ended for the day, we would continue to play, sometimes all day long. We would practice for six or eight hours, sometimes starting up again the next day. Even though Héctor was my teacher, he was like a part of my family. Not everyone has this experience. Sometimes the teacher does a good job in the classroom but doesn’t always go the extra mile. Héctor saw how committed I was to the music and to him as a teacher also. We still have some projects we’re working on together, planting seeds for the future.

From its beginnings, jazz has been a genre of music characterized by its diversity, with improvisation always having an important role. What does jazz mean to you, in terms of your musical development?

For me, jazz is a spectacular form of music. Clearly, mastering the technical aspects is critical. But beyond that, when you start to play a jazz number, there is a main melody, but it then becomes transformed. There are many varieties of composition, but that freedom leads into a sort of limbo, and a process begins that is more spiritual than theoretical. That’s the magic of jazz. It is creativity… And creativity comes from our own humanity, from our reality. It comes from what is genuine.

Obviously, there are many styles of music these days, everything from classical music to rap, but regardless of the genre, there are really only two types: good music and bad music. Good music is genuine. It is music that has the most substance. The reason bad music is bad is because it has no foundation, it has no essence, and ultimately it has nothing to say. When you have something to say, it is usually the people who are the most vulnerable, or the most sensitive, who can put that into their music.

Jazz is a philosophy of life, like a manifesto that is founded on the greatness of the masters. If you study the origins of jazz, going back to the 1930s, you can see that jazz is musical language passed on to the future. That’s why the educational aspect is so important. The masters must continue to pass on their knowledge to future generations, to establish a commitment to that same love and loyalty.

When you look back at your career so far, you talk about spontaneity, confidence, and talent. And also wisdom. What have you learned over the years, as a musician, a composer, and a winner of Latin Grammy awards?

I think the best lesson is that all the work you do has a positive result. I remember back when I was in junior high school, I was doing it for up to 12 hours a day, sitting under an enormous shade tree that grew behind my house. We lived by the ocean, in the house where my parents still live. There were guys around, and bad things were happening… but I spent my days under that tree instead, feeling the breeze and studying the music of Charlie Parker[i]. That was the tool I had available. In the neighborhood where I lived, I saw some of the other kids heading down the wrong path in life, and I said: that won’t happen to me. I knew that music was a way for me to do something else, so I wouldn’t end up like them.

I used to walk from my high school to the university. I don’t know how many blocks it was, sometimes up to four times a day, and that’s under the tropical sun of Puerto Rico! I still have the same saxophone I played back in school—in January I will have owned it for 31 years. I think that’s wonderful.

In a world as uncertain as ours, do you feel like music gives you some sort of refuge? Some sort of freedom or room to breathe maybe?

As soon as I open up my saxophone case, I feel more complete. It’s like an extension of me, and that’s why they call it an instrument, because it’s an instrument of the soul. If one day—and I hope this never happens—I no longer have the strength to blow into my saxophone. I’m sure I will still pick it up and hold it when I’m writing music, I will always have it. It’s not something separate from me, it’s a part of my existence. Music is not something I do, it’s something I am. In this world with so much uncertainty, there is obviously the very different, more commercial perception of music. But everything has its purpose. Music is like the ocean. Every wave travels a long distance before breaking on the shore. The sound of those breaking waves becomes something unstoppable, eternal, echoing throughout time and space. It’s not something you’ll hear for one month and then it’s gone, like a trendy hit song. When music is genuine, it is eternal. Mozart, Bach, Liszt, Chopin… It’s amazing how timeless their music has become.

[i] An American jazz saxophonist and composer, considered one of history’s greatest saxophone players. A key figure in the evolution of jazz and one of the genre’s most legendary and respected artists.

Let’s talk about Puerto Rico. How do you think life on the island has evolved for its people? Has being Puerto Rican had an important influence on your music?

Puerto Rico is where my memories are. The island may be most famous for its salsa music, or now for the style of urban music known as reggaeton… But it has many more traditional styles of music too. These can be roughly classified into three types: the traditional dance style known as Puerto Rican danza; the local folk music associated with the Puerto Rican cuatro, which is the national instrument; and Afro‑Puerto Rican music, which primarily has two styles: the Puerto Rican bomba and the plena. So how did those three genres began to mix? Because there are 3.5 million people, all very diverse, who are listening to all of those musical styles. What I am seeing in the educational setting is salsa groups, jazz groups, so many talented young people, and my view is that all of them are applying their determination and their efforts to share their music with the island and enhance its artistic scene. And I see this as a scene with so much resilience. In Puerto Rico I realize that there are so many college students who have two or three jobs, and they’re going to their classes too. There are some serious problems in the community—crime, child abuse, some terrible things—but I also see all the people who are getting up at 5 o’clock every morning to go to work, to give their family a better life, and doing it a way that is very authentic and admirable. People and artists are showing real-world proof of their effort. I think this kind of thing is happening all over the world. I have a friend in Poland who is experiencing the same situation. He’s an amazing musician, and he is selling pizza in the middle of the pandemic. Obviously, seeing things like this makes you think. I believe it all comes down to determination, the drive to become the best that you can be. We are all human, and being human means that sometimes we will fail. However, at the same time, being human means making the effort to look out for ourselves and stay strong in the face of any type of adversity. Our own personal dignity is really all we have.

Do you feel like you’ve been lucky, or do you think your success is your reward for working so hard?

The challenge never ends. Success comes from just staying in the game. Sure, luck exists, but what really matters is the ability to look inside yourself. After so many centuries of history the emphasis tends to be on looking outwards, to react to what is going on right now. But then you start to realize that there have always been some people who have looked inwards, and that’s the big difference. I try to focus on developing from the outside in, to see how much I can give.

And what do you find yourself thinking about the most right now?

I always have about 10 records playing in my head all at once, but right now we have a series of performances in a very special place called El Distrito, which is a new entertainment complex in Puerto Rico. It’s spectacular. It’s like an enormous outdoor music hall, with a huge dance floor. We are also going to have a big concert next year in New York, as part of a series of events taking place at the Lincoln Center[ii]. That’s what we have planned. If you’re going to be in New York, I hope I’ll see you there.

[ii] The Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, more commonly known as the Lincoln Center, is a complex of buildings in New York City with 61,000 m² of space. It is one of the world’s largest performing arts centers.