ESG regulation: bringing green to light

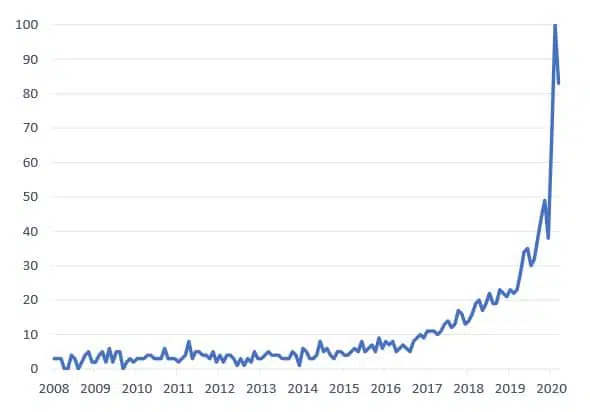

It is no wonder, therefore, that the number of online searches for the acronym ‘ESG’ has soared in recent years.

ESG: volume of Google searches

What measures has the European Union taken to promote this type of investment?

The rapid development of new financial products, the dynamism of the financial markets and the ambiguity surrounding the very definition of ‘sustainable’ have brought about a need for standardized regulation. In March 2018, the European Commission launched its Action Plan for Financing Sustainable Growth, which established ten key measures aimed at forging a connection between the financial world and the rest of society and the planet. This plan aims to:

- Reorient capital flows toward a more sustainable economy.

- Integrate sustainability into risk management.

- Foster transparency and long-termism.

The measures include, most notably, the creation of a label for sustainable products, the incorporation of sustainability into financial advice and the development of a unified classification system for sustainable activities, known as the EU taxonomy.

The taxonomy is a tool that aims to help investors understand whether an economic activity is environmentally sustainable, applying in the first phase of its rollout to climate change mitigation activities. For the European Commission, for an economic activity to be included in the taxonomy it must contribute substantially to at least one of the six environmental objectives (climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, the sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, the transition to a circular economy, pollution prevention and control, and the protection of biodiversity), must not significantly impinge upon the other five objectives, and must comply with the social guarantees established in the labor conventions of the ILO (International Labor Organization). The taxonomy will subsequently include activities of a social nature in later stages of its development.

The European Union has established its roadmap for fulfilling the commitments of the Paris Agreement and achieving climate neutrality in Europe by 2050 by means of a Green Deal that includes up to 50 policies and initiatives related to clean energy, sustainable transport, the circular economy, sustainable agriculture and building renovations. This grand plan has been boosted by being allocated 30 percent of the funds from the European Recovery Plan that was created to address the impact of COVID-19.

Why is the European Union turning to the private sector to achieve its sustainability goals?

On top of the need to fund these measures, the European Environment Agency estimates that between 2010 and 2019 natural disasters caused average annual losses of 12.5 billion euros. With this in mind, there is a strong argument for private sector participation in the efforts to halt the rising economic and social costs of climate change.

Who is invited to participate?

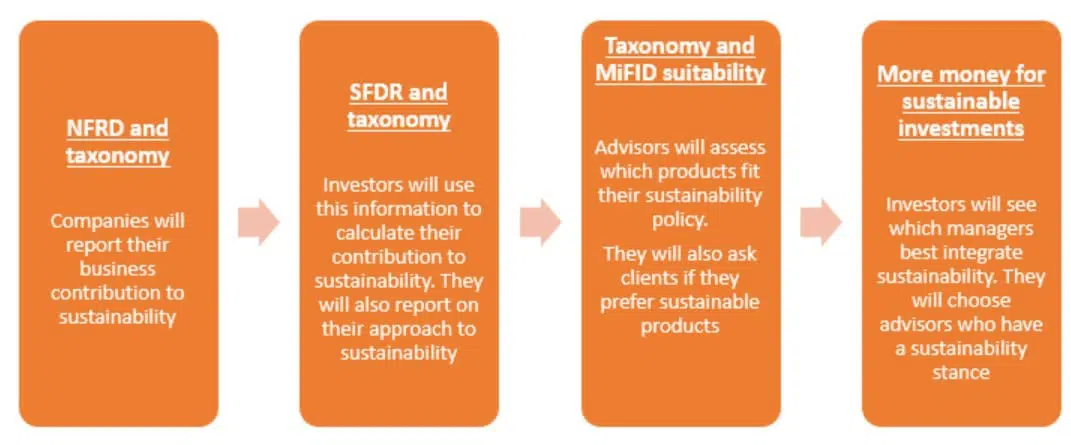

Companies, first and foremost. The entire information chain will begin with companies, as they will be required to report on how their activity contributes to environmental sustainability. At the forefront of the plan will be the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), which requires listed companies to report on the proportion of their economic activities that can be classified as sustainable with respect to the taxonomy, along with the Shareholders’ Rights Directive, which addresses sustainability from the perspective of engagement between companies and their shareholders.

Subsequently, asset managers will analyze all the information provided by companies and channel people’s savings toward sustainable investments. To this end, there will be a requirement for all investment products managed in the EU to be classified into three categories on the basis of the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which entered into force on March 10, 2021:

- Article 6 — products that incorporate sustainable risks (or that explain why they have not done so).

- Article 8 (light green) — products with environmental or social characteristics.

- Article 9 (dark green) — products aimed at sustainable investment (chiefly sustainability-oriented and impact funds).

The SFDR is therefore the EU’s proposed plan to address the issue of greenwashing.

Last but not least, financial advisors will analyze the information provided by asset managers to ensure compliance with the obligations set out by the SFDR for this group of professionals, who must:

- Report on how the company for which they work integrates sustainability risk into its advice and its compensation policy.

- Report on whether they consider the main adverse effects that their advice has on sustainability factors.

- Disclose the likely impact of sustainability risks on the profitability of the products that their advice relates to.

How does this whole flow of information work?

What risks could we face?

But there is still a long way to go, and the path ahead is not without its risks. No matter how many regulations are created, none of these directives will succeed if we forget that the ultimate aim of any investment is profitability. If we are able to keep this in mind when making sustainable investment decisions, we will be closer to enjoying the best of the worlds.

If, on the contrary, we raise sustainability standards too much, we would risk turning this into a mere regulatory exercise that is overly stringent with too strict a definition, thereby making socially responsible investment too small or too restrictive a category. In addition, this would discourage investment in sectors or companies that need to improve most with respect to ESG matters, which would hinder efforts to achieve the ambitious targets that regulators have set themselves.