TRANSFORMATION | 09.09.2020

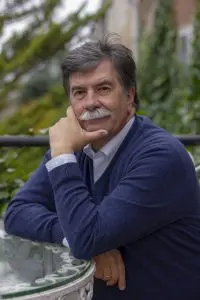

Javier Urra: “Childhood development requires face-to-face education.”

Interview with Javier Urra, Doctor of Philosophy and Doctor of Health Sciences, former Children’s Ombudsperson: “Children get used to wearing masks much more quickly than adults, they adapt; adults just don’t seem to get it.”

UNICEF warns that in order to ensure the right to education, we need to protect the right to health. In the current situation, where many countries are still a long way off from controlling infections, were you in favor of returning to the classroom?

UNICEF warns that in order to ensure the right to education, we need to protect the right to health. In the current situation, where many countries are still a long way off from controlling infections, were you in favor of returning to the classroom?

Undoubtedly, yes. It is absolutely necessary, especially in younger children because their cognitive, social and learning development depends on it. Children develop neurologically when they socialize with their peers, when they play, chat and debate. We have to learn to live with the pandemic and parents need guidelines, because it does not make sense to worry about teenagers going to school and then let them hang out with other children wherever they want. Children will test positive, as adults have been, and now is the time to explain to children that they should go to school. Should we be cautious? Everyone should be and should avoid coming into contact with grandparents and vulnerable people. Children often pick up on parents’ fear, and I think we are going to have a problem with school absenteeism. This can be managed in a hybrid way at university because young people are furthering their training and are not in the development stage.

“Children have to go back to school whether they like it or not”

Are you happy with a hybrid face-to-face/online model if the situation so requires?

I’m not too worried about physical attendance, they will touch, they will kiss no matter how alert the teachers are, but what we have seen so far is that the pandemic is brutal on the elderly, in aged care homes, but not with children. Naturally there is an economic concern. If children are in lockdown, then work suffers, as we have to work from home… This is our reality and we know that children usually spread all kinds of viruses. I think that there are clustered groups. I run a therapeutic center with 96 boys. We’ve been working in groups for 10 years and have come out of lockdown without a single positive case of infection. I know a lot of people are worried that children will fall ill. I’m very concerned that a teacher who has been in contact with other teachers will fall ill. If an evaluation board is organized for a center’s entire faculty, and one positive case is identified, everyone will have to go into isolation. This is where we have to be smart, be creative and design shifts to reduce contact as much as possible.

With no after-school activities, with reusable spaces, planning alternatives to school transport, to school dining rooms… Do you think that the urgency of the current situation will help spark innovation for a dormant education system?

Yes, a dormant system. At first it was the shock. Everything was paralyzed and there was no leadership. We now know that this is going to be with us for quite some time. We still don’t have a vaccine and it’s uncertain whether one would be able to save us all anyway, so we have to think about how we can live together with the lowest possible risk. But there are contradictions. We need to go out, we need to go to the stores, we have to preserve economic activity. Grandparents are the ones at risk when in contact with children. When families had scheduling problems or children suddenly fell ill in the past, they turned to grandparents for help. We can’t do this now and it is very difficult when you can’t rely on grandparents for help. Society has lost skin on skin contact, the desire to kiss and we definitely have to respect intergenerational contact.

Are we facing a paradigm shift in our family relationships while seeking to return to old customs? How do we adapt working conditions?

Together with sociologist Enrique Domingo and the Director of Educar es Todo (Education is Everything), Leo Farache, who’s a great communicator, we created the Instituto de Conocimiento Mar de Fondo (Sea of Knowledge Institute) a few years ago. We launched a study based on 4,000 interviews in Spain about priorities in Spanish people’s lives. We were going to present it on March 14, but we were unable to due to the circumstances. We re-did it later on and what’s really surprising is that the answers are almost identical. Nothing has changed since lockdown. Preferences—beliefs, values and attitudes—are the same. Behaviors, mannerisms, remote working have varied, but our preferences haven’t. Humans adapt to some things, but we maintain our pillars and structures. Are you going to work remotely, share the task of bringing things home, stay more within your neighborhood and use your car less? Definitely. But in terms of preferences, people don’t really tend to change, because this gives us security, especially so in times of uncertainty like now. It is a huge, very interesting job that has required a lot of time and a lot of effort. The team has been great and, unfortunately, we haven’t had any financial support.

As parents, how can we support the return to school? Are our little ones stressed too?

Some children do tend to be obsessive or compulsive. But, in general, they have a great advantage over adults: they don’t dwell on the past or anticipate the future. They live in the present. This disappears as soon as they are with other children. But some parents are very worried and their children pick up on this. Some children really need school, particularly the youngest, those who require special education. Stress? The logistics system for distributing food and technology has worked very well. We haven’t dropped everything, but our society hides death away—we haven’t seen many images. We’re almost living in a dream. I wrote a difficult article asking why we have made a great tragedy such a festive event. The answer is that there are interests, fears and a social reality that says, “Well, it was old people who died.” As if life had suddenly been cut short. If it had been 40,000 young people, society wouldn’t have put up with it. This leads to ethical questions. We are faced with many dilemmas and interesting questions surrounding loneliness, silence and how this has been experienced in various couples and family relationships. This is a perplexing situation that will take us several years to analyze.

“We’re almost living in a dream. I wrote a difficult article asking why we have made a great tragedy such a festive event.”

You stress that, excluding other health conditions, lockdown has not left a significant mark on children. What would you say about this so-called new normal? Do you think that young people will have become used to seeing the world through a mask?

The mask is the least of it; it is more about the habit. Children get used to wearing masks much more quickly than adults, who have spent much longer living without masks. Children adapt better. Adults just don’t seem to get it compared to children; they believe they are suffering more. No… No, if children fall down, they get back up. We have to explain things to children. Whether son or daughter, or student, there’s light at the end of the tunnel. If we beat this by March next year, in three years’ time, we’ll look back on this as a distant, hazy memory. That is another human characteristic: makeup.

If you could, how would you reform education? What would schools look like in the future?

A government agreement, like the one that was attempted, and I know we were close. An agreement that avoids the struggle between public, private and subsidized schools; where the vernacular language of each region is seen as an enrichment, while continuing to maintain a language spoken by 500 million people, with respect for transcendence, spirituality and philosophy and with a love of language and expression that allows us, like right now, to convey what we truly think and feel. And with a focus on developing emotions and feelings, if I may, thinking about how we educate girls—there are hardly any women in jail—and boys. Sensitivity is the essential challenge and let’s get rid of the term Artificial Intelligence. There may well be algorithms, a computer memory far more superior than that of human beings, but humans can cry when they are happy, when fondly remembering a friend who has died. No machine could ever understand that.

You were president of the European Network of Ombudspersons for Children. Which other models give better results in terms of resilience, flexibility and commitment?

We are a Mediterranean people; we have a great culture and history. I wouldn’t want to stray too far from there. But what I would do is rapidly increase investment in education. Spain doesn’t have any universities among the top 200. But we have to look at what universities such as Yale, Harvard and Oxford do. It’s very difficult to compete against the best on such a small budget. I believe that if we truly believe in education, we have to support it. Parents should be helping teachers, but for that we need culture. We’ve barely scratched the surface in terms of education. We’ve got a lot of problems. We have to cultivate a love for education and learning through every stage of life.

As a society, what do we need in our backpack for this course? Dialog, consensus, long-term vision, technological investment, psychological support—the list goes on.

Hope, optimism, a dash of humor, work, work, work. We should be less critical and more collaborative, do our best and be generous. We know that some people will be very selfish and short-sighted, but others will give everything they have to society. And, from there, emphasizing that what really matters is “we,” not “I.” Everyone living through the pandemic will die one day. That’s just how it is. We can’t be governed by fear. We’re going to experience severe economic situations. There will be unemployment and people won’t be able to pay their rent. These are the times when we need to show that we can adapt, not just states and governments. If someone is about to lose their job, let’s lower their salary. We can’t keep thinking “It’s not me, it’s society.” It affects us all. We have to come through the other side together.

If the effort to return to school as normal fails, what can we expect from similar situations in the future? Will contingency plans change?

The subjects that need to be studied; the essentials will stay the same. The way we give classes, whether face-to-face or by Zoom or Skype, is what changes. Passion for learning is instilled by being in front of a screen, not behind one. But I think children have learned a great deal, because they have seen their parents be nervous, they have seen their parents cry, because they have shown tenderness. Yes, they have missed out on part of the curriculum, but they have matured, because that’s what happens in extreme circumstances.

How do we approach leadership, discipline, responsibility and respect? Is the world ready for what lies ahead?

Things are dire at the political level. There is very little guidance and very few individual ideas. Everything about what the boss or the group says is very over the top, and very contradictory. And this is happening at a time of great uncertainty, where creativity, lateral thinking and alternative thinking are required. The world has no leadership. We’ve lost the great statespeople. This has to make us stop and think about how the system works. But some major businesspeople are managers. Perhaps they could provide solutions for situations that require management capacity, realistic analysis and economic management. Companies are hitting potholes and are very clear where they need to go, what they need to do and where they need to incentivize and open up new fields of work. That is truly essential. I think that society has largely lost confidence in its representatives, and that is worrying.

So what do we do? Who do we listen to?

This is where we have to respect opinions. I’m not an architect. I can give an opinion about the building I live in, but it doesn’t matter much. We have to give a voice to those who know what they’re doing, those who have studied their craft, otherwise there’s just a whole lot of noise. Opinion is democratized. I think what we actually need to democratize is meritocracy, effort, because if not, we are continually setting the bar lower.

Related articles:

Balance or a balancing act? The challenge of ensuring comprehensive education in a pandemic